The Stained Glass Window

May is Mental Health Month. As someone who has lived with anxiety and depression since my teens, this topic is very near and dear to my heart. I know that I am fortunate to get the care I need in the times that I struggle. Unfortunately, there are many who aren’t always as lucky. Please understand that you are not alone in your journey. You can visit the website nami.org for resources and to learn how you can advocate for yourself and your loved ones with mental illness. I would like to share an essay about an experience I went through in March of this year below. It’s taken me more than two months to be able to reflect upon this, but I knew it was finally time.

It was raining the day 18-year-old Isaac was laid to rest. We joined the mourners that afternoon, carefully walking around the murky mud puddles that pooled on the concrete of the church parking lot. I could see my reflection in those pools, and the tears threatening to spill over onto my cheeks, on that day as I struggled to keep my umbrella from blowing inside out and out of my hands.

In a matter of a few days, the world had become a confusing, broken and upside-down place, one that I hadn’t lived in for a very long time. It started with an e-mail from our church pastor, letting us know one of the longtime members of our youth program and church had passed away. There were no other details, except the request for prayers for the family. I read the e-mail as I waited to pick up my 14-year-old son from school. When he got in the car, I told him what I had just read.

“What do you mean?” he asked me, frowning. “Was he in an accident?”

“I don’t know,” I told him, with a familiar, sinking feeling weighing on my heart.

My son pressed on. “Suicide?” he asked, looking out the window. “That doesn’t make sense,” he continued, talking more to himself than me. He mentioned how this boy had just gotten into his dream college. We drove home in silence, contemplating.

Our worst fears were confirmed. It was indeed the thief of suicide that took this young person from the family and friends that loved him. Worst of all? No one knew why. They had no idea. This young man had suffered for so long but didn’t want to burden those around him. It’s a story we hear time and time again, but it never gets any easier.

As we learned of the funeral arrangements and read the beautifully-written obituary celebrating this young man’s life, my heart felt like it was broken in a million pieces. I was immediately transported back to the mental health facility I had walked into at the age of 20 years old, when I confessed to my roommate that I no longer wanted to live.

I knew the pain he must have been feeling. I knew how hard it can be to tell someone what the pain feels like—a pain that seems to come out of nowhere and has no rhyme or reason. It leaves you with an ache, a pillow full of tears night after night, a loss of appetite and the inability to understand who the person is staring back at you from the mirror.

We walked through the lobby of our church the night of his visitation, looking at the enlarged pictures of a smiling young man wearing a Tommy Bahama shirt, holding a selfie stick as his brilliant smile joined those of his friends, and even a shot of him decked out in scuba gear, giving a thumbs up to the photographer in an underwater shot.

“My, how he lived,” I thought to myself, then stopped. He had lived, but he hadn’t lived long enough. I wondered if I were able to talk to him at that moment, would he have regrets? Would he be grateful the pain was over, or would he have wished he could have held on just a little longer?

I think about the holding on part often. It’s what I did for most of my early 20s—white knuckling through the depression, anxiety, insomnia and sleepless nights. There were times it was excruciatingly hard, and I didn’t think I would make it through, but I pushed myself to hold on.

Hold on, I would say to myself, in between therapy sessions, in between new trials of antidepressant medication. Things will get better. There are people who love you, even if they don’t always know the best way to show it. You have so much to live for, even though it doesn’t seem like it now.

We drove home from the visitation in silence. I could hear my 16-year-old daughter’s ragged breaths from holding back tears. My son had only one question, “Was that his body in the coffin?” It was almost as if he couldn’t grasp that Isaac was truly gone until he saw that.

The rain poured outside the following day as the hundreds of people gathered inside the red brick church to celebrate Isaac’s life. We heard stories of his most epic pranks, his love of politics and sports, the way he lit up every room he walked into, and his endless generosity. I thought to myself how the young men in their neatly-pressed suits did not deserve to have their friend taken away by mental illness. How unfair it was that they were carrying their friend to his final resting place, far too soon. I thought of the quote I had come across the day before.

Love conquers all things except the fact that depression is not a thing, it’s a living force that consumes everything in its path, it takes no prisoners.

Isaac was a prisoner to his pain, and it took him from the world. I wished he were sitting beside me so I could’ve taken his hand to tell him things can get better; they will get better.

I wished I could have told him he wasn’t alone, because I’m sure that’s how he felt.

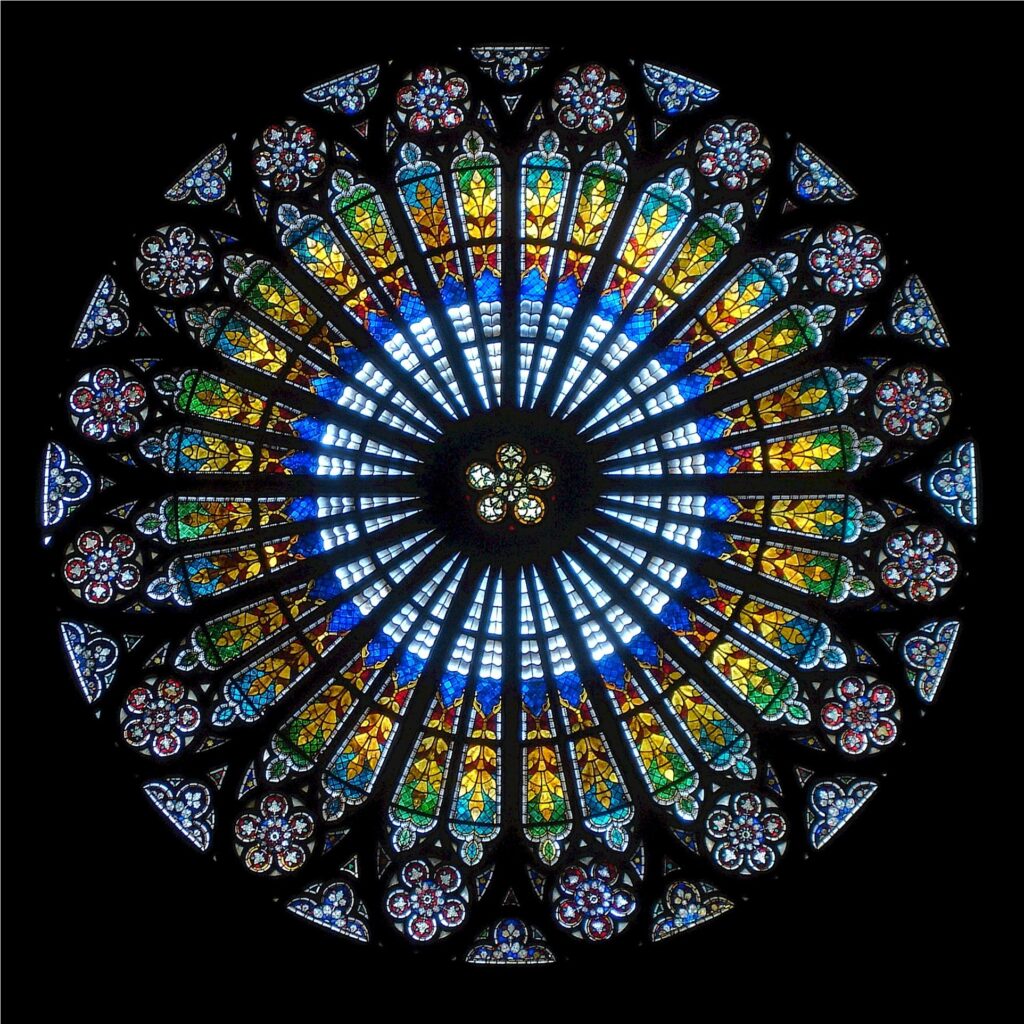

As the service ended, I looked up at the beautiful stained-glass window at the front of the church sanctuary. I could see the sunlight begin to stream through it. As we walked out of the church, the sun shone down upon us, and we gripped the handles of our umbrellas we no longer needed tightly as we made the long walk to our car. I watched as the humidity formed steam off the stagnant puddles of rain. A bright blue sky unfolded above us. I couldn’t help but feel like Isaac was giving his loved ones a final message as they said their goodbyes.

I’ll be okay now.