Book Review: Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix

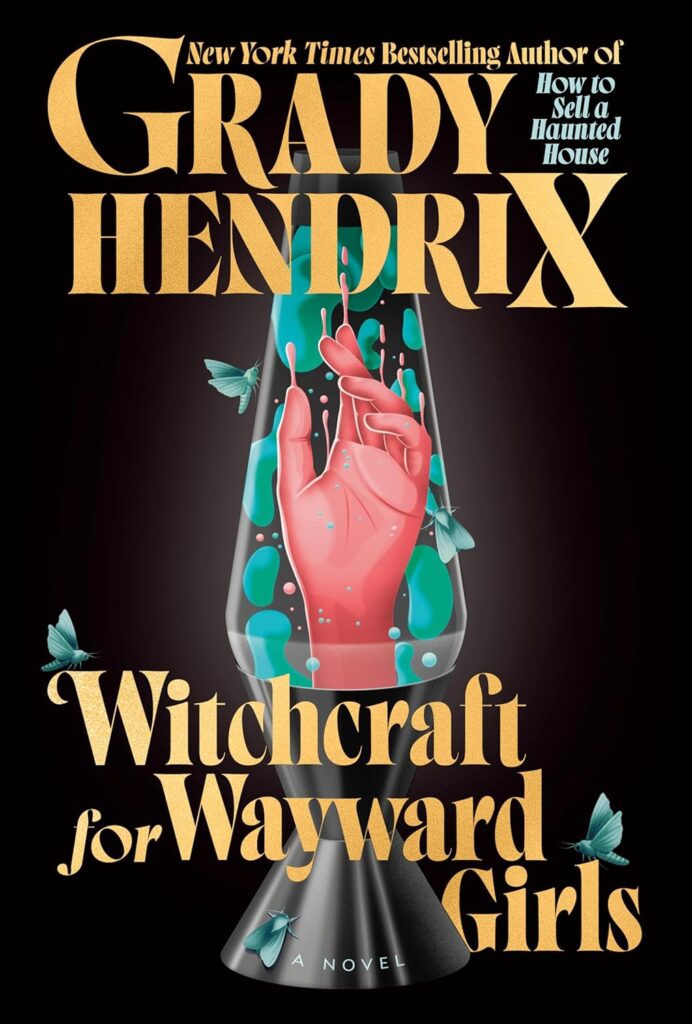

Several months ago, I was browsing the shelves of Barnes & Noble when I noticed the book Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix on an end cap. The illustration with the lava lamp instantly caught my eye, and having read The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires several years ago, I knew it would fall into the horror category. I immediately opened my Libby app and requested the book, noting that I would be waiting a few months before it came available.

Synopsis:

They call them wayward girls. Loose girls. Girls who grew up too fast. And they’re sent to the Wellwood House in St. Augustine, Florida, where unwed mothers are hidden by their families to have their babies in secret, give them up for adoption, and most important of all, to forget any of it ever happened.

Fifteen-year-old Fern arrives at the home in the sweltering summer of 1970, pregnant, terrified and alone. There, she meets a dozen other girls in the same predicament. Rose, a hippie who insists she’s going to keep her baby and escape to a commune. Zinnia, a budding musician who plans to marry her baby’s father. And Holly, barely fourteen, mute and pregnant by no-one-knows-who.

Every moment of their waking day is strictly controlled by adults who claim they know what’s best for them. Then Fern meets a librarian who gives her an occult book about witchcraft, and power is in the hands of the girls for the first time in their lives. But power can destroy as easily as it creates, and it’s never given freely. There’s always a price to be paid . . . and it’s usually paid in blood.

When the book became available, I started it immediately. I wondered how a white male author would tackle the heartbreaking topic of maternity homes, which were most prevalent in the United States between the years of 1943 and 1973. Grady Hendrix writes in the acknowledgments that in his early 20s, he learned about two female family members who’d been sent to maternity homes as teenagers and given their babies up for adoption.

He said:

Whether girls had been raped or sexually abused, believed a promise that wasn’t kept, didn’t have access to contraception, or simply didn’t know it existed, they were told that getting pregnant was all their fault. Doctors and social workers labeled unwed mothers ‘neurotic,” newspaper columnists suggested they be housed in Alcatraz, and politicians blamed them for everything from high taxes to crime to the collapse of Western civilization.

I imagine the author had no idea Roe vs. Wade would be overturned by the time it was published, putting many of the women in our country right back into the book’s setting in 1970.

But I must hand it to him—Grady Hendrix knows how to write women. Much like the Charleston, South Carolina women in The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, each female character in Witchcraft for Wayward Girls is beautifully written, strengths and flaws and all. Through the stories of the four main girls—Fern, Zinnia, Holly, and Rose (each girl is given a pseudonym when she arrives at Wellwood House).

There’s a lot to take in with this classic “monster in the house” story, from the judgmental and stern Miss Wellwood, to the on-site Nurse Kent, to Diane, the social worker who explains to each girl why it’s in the best interest for them to give their baby up for adoption, and the older Dr. Vincent, who makes sure to tell every girl exactly what he thinks of them as they are at their most vulnerable in his exam room.

Hendrix also deftly explores class in the 1970s south with characters like Hagar and Miriam, the two Black sisters who work as the cook and housekeeper in the home. Having lived in St. Augustine their entire lives, they are very familiar with “root work” and “witchcraft” and serve as the antithesis to Miss Parece, the librarian who ends up enticing the four main characters with a book called How to Be a Groovy Witch.

As with some of his other titles, I feel this book could have benefitted from some paring down, particularly in the last quarter of the book. I’ve also warned friends that there are some disturbing scenes of childbirth (imagine what the lack of empathy in a delivery room setting would look like, especially with doctors and nurses who believed the teenage mother to be merely a vessel for delivering a baby).

Overall, I felt it was an interesting take on the role of maternity homes throughout history, and an empathetic exploration of how conflicted a mother with little to no resources can feel when faced with the pressure to give her baby up for adoption.